Editorial

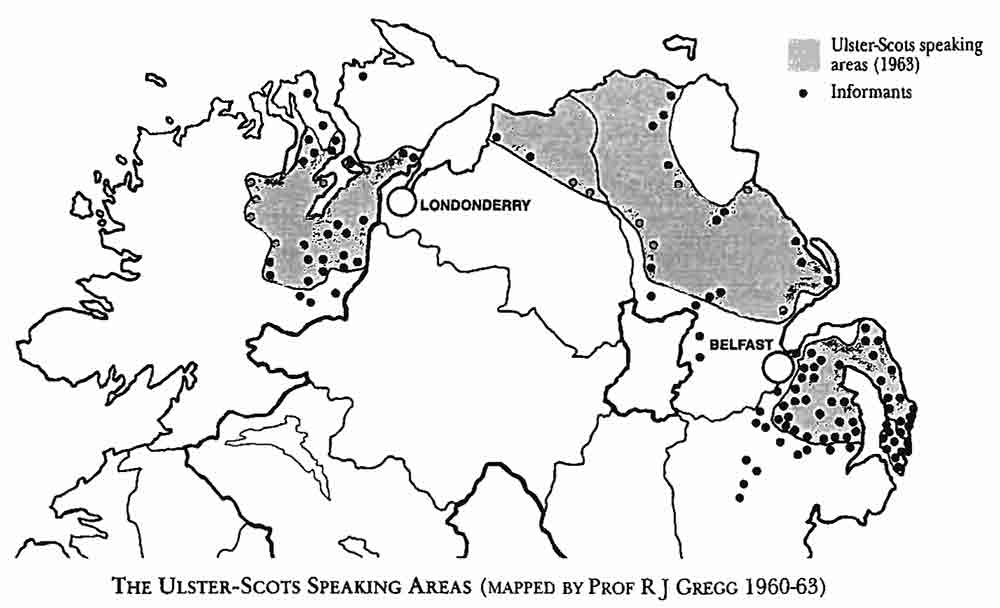

There have been so many important developments in relation to the Ulster-Scots language movement since the appearance of the last issue of Ullans that an extended editorial is necessary. On the positive side, recognition of Ulster-Scots as a European Regional Language is now official and its future secured in terms of official support in the context of both the equality agenda and the European dimension. However, on the down side, the year also saw the death of our President, Professor R. J. Gregg. A tribute to Professor Gregg by Professor Michael Montgomery of the University of South Carolina is included separately, but the entire society would also wish to acknowledge the enormous debt we owe to our founding President. To ordinary members, unfamiliar with his specialist academic work on Ulster-Scots pronunciation and vocabulary, he will remain best known for his pioneer work mapping the distribution of Ulster-Scots speaking areas. His extensive research into word distribution formed part of his PhD thesis, entitled “The Boundaries of the Scotch-Irish Dialects of Ulster.”

He published his map in 1963, and when it appeared in Ullans number two, the society was criticised by Irish language enthusiasts. Professor Gregg was so outraged by this criticism of his original work that he requested any republishing of his own work to substitute the title “Ulster Scots” for “Scotch-Irish” — and, where ambiguity existed, to substitute “language” for “dialect”. Professor Gregg’s enthusiastic support for Ulster-Scots language planning remains a cornerstone of the entire language movement. It is fitting that the tribute to him should be penned by Professor Michael Montgomery, his co-author of “The Scot’s Language in Ulster” in “The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language”, C. Jones (ed) 1997.

1. Ulster-Scots and the Political Process

The language movement has been the butt of many unfair criticisms, ranging from “a DIY language for Orangemen” to “a political gimmick to impede the progress of Irish”. Nobody who has followed the Ulster-Scots language movement’s involvement in lobbying for language rights could subscribe to such views.

The Ulster-Scots Language Society is non-political and non-sectarian in membership, aspirations and constitution. We have sought equal status and rights with Irish and have never sought to diminish the latter. The only means of de-politicising both Ulster-Scots and Irish in the present context is through the equality agenda within Northern Ireland and by affording Ulster-Scots equal status in Europe as one of two regional minority languages in the island of Ireland.

In practice this means that we will endeavour to ensure that the Ulster-Scots language is treated in exactly the same way in Northern Ireland as the Irish language. In the event of the establishment of a North-South Body on language, with separate Irish language and Ulster-Scots wings, we will endeavour to ensure that Ulster-Scots and Irish are also treated on an equal footing in the Irish Republic. Following the UK Government’s signing of the European Charter on European Regional Languages, we will insist that the different provisions of Part Two status for Ulster-Scots and Part Three for Irish are not used to justify or institutionalise differential treatment. Such actions by government would be in contradiction of the spirit of the Charter and of the equality agenda in the Belfast Agreement.

2. Status, Recognition and Education

At the core of the Belfast Agreement of 10 April 1998 was a commitment to “partnership, equality and mutual respect as the basis for relationships within Northern Ireland.” It also recognised “the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.”

The then Political Development Minister, Paul Murphy, announced on 4 June 1999 that “the Government has decided that Ulster-Scots in Northern Ireland will be recognised as a regional or minority language for the purposes of Part II of the Council of Europe Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.” He linked this announcement firmly to the terms of the Belfast Agreement when he stated: “The importance of respect, understanding and tolerance of linguistic diversity in Northern Ireland was explicitly identified in the Good Friday Agreement. I am pleased to announce these significant developments which take this commitment forward.”

Under Article 7 of the European Charter, the government commits itself to:

- Take resolute action to promote the Ulster-Scots language;

- Facilitate and/or encourage the use of Ulster-Scots, in speech and writing, in public and private life;

- Make provision for appropriate forms and means for the teaching and study of Ulster-Scots at all appropriate stages;

- Provide facilities to enable non-speakers to learn Ulster-Scots if they so desire; and

- Promote study and research on Ulster-Scots at universities or equivalent institutions.

The wording is indicative of the heavy responsibility placed upon the education sector in the delivery of these objectives. We would, however, suggest that the achievement of the wider aim of mutual respect requires an even more comprehensive approach, embracing language, literature, history and culture.

Meanwhile, the Department of Education has issued a report entitled Towards a Culture of Tolerance: Education for Diversity. This document in its turn makes a commitment to mutual understanding and respect for diversity, and recognises the need for change in the curriculum and in the training of teachers to deal with such issues. In welcoming this, we would reiterate our belief that Education for Mutual Understanding (EMU) can only be delivered within a culturally inclusive education system that tolerates, respects and treats fairly the three main cultural traditions present in Northern Ireland society: Ulster-English, Irish, and Ulster-Scots.

Thus far, the English and Irish languages, literature and history have been accommodated at GCSE and “A” Level in schools, and at degree level and beyond in our universities. Meanwhile, the Ulster-Scots tradition has been completely excluded, without provision for its serious academic study at any level.

A review into this, as it relates to schools, must ensure that all children are treated equally and that all have equal access to their history and traditions. There must be a clearly visible change from the former offensive and demeaning situation, in which the other two main traditions were included while Ulster-Scots was excluded. As has been stated in another context: the status quo is not an option.

Children must be given access to their own traditions, language, literature, history and culture. In this, it is of prime importance that these subjects do not undergo a reinterpretation in the process of their delivery. The channels through which they are communicated must therefore be untainted by apathy, cynicism, ridicule or outright hostility. Only if their traditions are accepted within the curriculum and the school system in general will all our children grow in self-confidence and in their sense of belonging. The development of tolerance, respect and mutual understanding in children in the school system is dependent on the extent to which schools show tolerance, respect and understanding towards the children.

The Ulster-Scots Language Society is proposing the adoption of two initiatives within the primary school curriculum, and four in the curriculum for the secondary sector. Until these issues are satisfactorily resolved, we are suggesting that the EMU scheme should address the problem in the short term by engaging in single cultural identity work with children. There is ample precedent for such an approach in community relations work with adults.

3. Obituary — Robert J Gregg

Michael Montgomery, University of South Carolina

With the recent passing of Professor Robert J Gregg, the Ulster-Scots Language Society has lost a great friend and its first and only Honorary President. His loss will long be mourned in both his native Ulster and his adopted Canada. Though he left his homeland for opportunity abroad like many compatriots over the centuries, he remained a son of Ulster to the core. In British Columbia he found a distinguished career in his chosen field of linguistics, but devoted most of his scholarly writing to Ulster-Scots and remained a keen student of Ulster speech and local history throughout his life. His investigations of the Ulster-Scots language laid the groundwork for all who have come after him — linguists, geographers, historians, and others. It is due almost entirely to him that research on Ulster-Scots was put on a sound academic footing and that scholars elsewhere have learned of the existence of the language. It is not too much to say that he founded Ulster-Scots studies.

Born in Larne, County Antrim, in 1912, Robert Gregg was fond of saying that he was a native speaker of “urban” Ulster-Scots and that he did not begin learning “rural” Ulster-Scots until the age of four from elderly relatives in Glenoe, his mother’s home. Natural linguist that he was, he soon became fluent in the traditional variety of the language through summer visits with kinfolk, and it was no doubt the youthful experience of learning both standard English and Ulster-Scots (and continually contrasting the two) that sparked his curiosity about language and led to a successful career teaching languages and linguistics.

After receiving a B.A. with Honours in French and German from Queen’s University Belfast in 1933, Gregg enjoyed a successful career as a language teacher in Northern Ireland for two decades. Following five years as Senior Modern Languages Master at Regent House in Newtownards, he served as Head of the Modern Languages Department at Belfast Mercantile College from 1939 till 1954, teaching French, Spanish, German, and Russian. During these years he also studied Latin and took a B.A. in Spanish from the University of London. In 1954, having determined to pursue an academic career abroad, he emigrated to Vancouver with his wife and young family and was appointed Assistant Professor of Romance Studies at the University of British Columbia in January 1955. Over the next quarter-century he taught at that institution, becoming Professor of Linguistics in 1969 and serving as Head of the Department of Linguistics from 1972 till 1980, when he retired. At UBC he taught French, phonetics, dialectology, and many other courses, edited the Gage Dictionary of Canadian English, directed two major surveys of Vancouver and British Columbia speech, and was active in numerous professional organizations.

Foremost, however, Gregg was a student of Ulster-Scots. As a young man travelling about the province and becoming acquainted with the historical landscape of Ulster, he began to map the Ulster-Scots territory in his mind (ideas that were to mature into a thorough investigation for which he was awarded a Ph.D. from Edinburgh University in 1963). His first formal study of Ulster speech came in 1951 when, as a member of the Belfast Naturalists Field Club Dialect Section, he began collecting material for an “Ulster Dialect Dictionary” and collaborated with the Linguistic Survey of Scotland at Edinburgh University, which had included parts of Northern Ireland in its project. In the process he met Angus McIntosh, under whom he would complete his doctoral thesis, “The Boundaries of the Scotch-Irish Dialects in Ulster.”

Gregg’s principal achievements were to provide a comprehensive structural description of Ulster-Scots and a detailed mapping of where it was spoken. In other words, he identified the distinctive patterns of Ulster-Scots, how these differed from other varieties of speech in Ulster, and where these were spoken in parts of counties Down, Antrim, Derry and Donegal. Over many long months (primarily during a year’s leave of absence from his university in 1960-61) Gregg travelled the Ulster countryside, tirelessly interviewing over one hundred older, traditional speakers in order to pinpoint the geographical boundaries of Ulster-Scots. The result was a study unprecedented and unsurpassed in detail even today in the British Isles. Having long pondered the matter and studied the Plantation settlement of Ulster and finding some in Edinburgh to be sceptical of the vitality of the Scots language in Ulster, he was determined to outline the Ulster-Scots territory as precisely and meticulously as possible. The map he produced became a classic and continues to be cited and reproduced by scholars.

Throughout his years in Canada Gregg kept in close touch and collaborated with colleagues back in Ulster. He participated in the conference inaugurating the Ulster Dialect Archive at the Ulster Folk Museum in 1960. For a time he was co-editor with John Braidwood of the Ulster Dialect Dictionary project inherited from the BNFC. When the Department of Education in Northern Ireland commissioned the Concise Ulster Dictionary in 1989, he was pleased to be enlisted as a consultant and in succeeding years donated much of his own material to the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, where the volume was being edited. He took particular delight in being honoured by the Ulster-Scots Language Society with its Honorary Presidency.

I knew Robert Gregg the last decade of his life, mainly through correspondence and telephone conversations. It was my privilege to collaborate with him on the “The Scots Language in Ulster” chapter in Jones (1997). I met him only once, but that was one of the more memorable events of my career. Both of us were attending a conference on dialectology in Bangor, Wales, in 1987. While other conferees took a mid-week excursion he agreed to meet me for a few minutes to answer some questions. I was a young scholar planning to visit Northern Ireland the following year and begin studying the influence of Ulster speech on my part of the world, the American South. I wanted his advice on where in Northern Ireland I should go to do research and whom I should consult. What began as an afternoon chat turned into a session that ran through the dinner hour and far into the evening. My questions opened an incredible storehouse of knowledge in his head, as he began telling me of obscure novels to read, unpublished materials in the Presbyterian Historical Society to consult, and on and on. During these hours he gave me a blueprint that I began to follow the next year and have pursued ever since. Though I was a stranger to him and had never been to Ulster before, he shared with me everything he could. Such was his generous nature and such was his passion for his native soil. He was a proud man but made others proud to know him.

4. Encouraging Signs?

Status and awareness-building for Ulster-Scots has continued apace with more erection of Ulster-Scots names signs, the use of Ulster-Scots in multi-lingual documents by government bodies and the recruitment of an Ulster-Scots transcriber to record the proceedings of the Northern Ireland Assembly. All this has been important for Ulster-Scots and its speakers. It gives recognition and status to the language. It is the start of an acceptance of Ulster-Scots into public administration which will help to ensure the prestige and development of the language. It also begins to extend the areas of use of Ulster-Scots beyond that of the home and private relations.

Most Ulster-Scots speak English “in public”, so this “official” use of Ulster-Scots is necessary if its status as a European minority language is to be raised to an equal footing with Irish. It is a way for our country as a whole to say that it respects the identity, roots and cultural heritage of all citizens within the community. It is a mechanism for a majority to indicate tolerance and inclusiveness for a minority with a different culture.

Extending the use of Ulster-Scots into the public domain is adding to its status and prestige. Giving it some official status will help it to survive. If Ulster-Scots is left to be used only within the home, it will be denied the chance to evolve and develop the vocabulary needed to deal with all aspects of our everyday life as it changes.

Of course, official publications in English, Ulster-Scots and Irish such as those produced by the Arts Council, Belfast City Council or the Equality Commission are not, strictly speaking, necessary — for no Ulster-Scots or Irish speaker is unable to read or understand English. The use, like that of public signage, is symbolic. Is it a waste of money? When a Canadian Premier was asked if Canada could afford English/French bilingualism, the response was — “we can’t afford not to do it”. If Ulster-Scots and Irish are to be afforded equality of treatment and status, and to be de-politicised, we too cannot afford to have just Irish-English bilingualism.

Ulster-Scots has been excluded and stigmatised. However, the new status-building developments are helpful and they make good political sense. It is also recognition that the Ulster-Scots tradition is a part of the whole range of cultural diversity that exists across Ulster (including Donegal). With an end in sight to the marginalisation of the Ulster-Scots community, its traditional language can now be developed to the point where it is treated equally with Irish throughout the island.

Next: Ulster-Scots: View from Donegal

Previous: Contents

Contents: Ullans: The Magazine for Ulster-Scots, Nummer 7 Wunter 1999