Murdoch’s Manuscript — An Early New Testament in Scots

Author: Mark Thompson

Date: 2012

Source: Ullans: The Magazine for Ulster-Scots, Nummer 12 Wunter 2011/12

Mark Thompson

Introducing Murdoch Nisbet

In the late 15th century, there lived a man in Ayrshire called Murdoch Nisbet. The area in which he lived, Hardhill, is subsumed within the modern Newmilns, which is located on the Kilmarnock to Strathaven road, about halfway between Galston and Darvel. Not far to the east on that same road is found Drumclog, where almost two centuries later, in 1679, the Covenanting army was to win a significant victory against the forces of ‘Bonnie Dundee’ (known to the Covenanters as ‘Bloody Claverhouse’).

It is believed that Murdoch Nisbet was born about 1470, and died in 1558. To put his lifespan in context, the great reformer Martin Luther was born in 1483, and nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the parish church in Wittenberg in 1517. The times in which Nisbet lived saw the dawn of the Reformation. Indeed, he upheld the religious views of John Wycliffe (c.1328-1384), who was known as ‘The Morning Star of the Reformation’. Wycliffe’s supporters were called ‘Lollards’, and those who lived in the particular district inhabited by Nisbet were designated the ‘Lollards of Kyle’.

The Lollards held to a fairly wide range of other essentially Protestant beliefs, but for our purposes it is sufficient to note that they shared Wycliffe’s high view of the veracity and primacy of scripture. Wycliffe had been the first to translate the scriptures into English. Clearly, Murdoch Nisbet, as a Lollard, sought to follow his example and put the scriptures in Lowland Scots into the hands of his countrymen.

Nisbet must also have had an education that fitted him for the task in hand. Although details of his life are sketchy, we are told that he was a ‘notary’. These were people who were publicly authorized to draw up or attest contracts or similar documents, to protest bills of exchange and so on, and to discharge other duties of a formal character. Notaries public had existed in Scotland since the 13th century, and all Scottish solicitors were automatically notaries. Because of his job, Nisbet would have been well used to ensuring precision in the documents he wrote.

Protestantism in Scotland before 1470

Protestant ideas were not new to Scotland: there had been some Protestants in Scotland before Murdoch’s time. For example, an English ex-Franciscan monk, James Resby, had been burned at the stake in Perth in 1407; and around 1433 a Bohemian/Czech Protestant called Paul Craw had been burned at the stake in St Andrews.

We are not given any hint about when and in what circumstances Nisbet embraced the cause of Lollardry. Clearly, however, at this early stage in the spread of the Reformation, many more years would elapse before the all-pervading influence of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland was dissipated. It is certain that Murdoch Nisbet would have held very strong Protestant convictions.

Persecution of the Lollards

The Lollards, as itinerant evangelists with deeply held anti-clerical views, would have been a particular thorn in the flesh of the established church of their day. Also, they were viewed as subversives by the authorities.

It is no surprise, therefore, that we find in 1494 a group of 30 Lollards of Kyle summoned by the Archbishop of Glasgow to stand before King James IV of Scotland on a charge of heresy. The charges were dismissed, but it was a sign of the times. Murdoch Nisbet is known to have ‘fled over seas’. Because his life story is far from complete, we cannot be certain of his destination. However, given that he was only about twelve miles from the Ayrshire coast, it would not involve too much of a leap of faith to conclude that there is a distinct possibility that it was to Ireland that he fled.

Murdoch’s life’s work — translation of the New Testament

Wherever Murdoch Nisbet ended up, whether it was England, Germany or Ulster, he took with him a manuscript on which he had been secretly working — a translation of the New Testament into vernacular Scots. He translated from Purvey’s 1395 revision of Wycliffe’s Bible. It is not known how long Murdoch was away from Scotland, but when he came back, together with some other Lollards who had also fled, the persecution was still continuing.

Nisbet probably returned to Ayrshire in the 1520s, to a Scotland where Patrick Hamilton would be burned at the stake in 1528, where two other Lollards (Jerome Russell and 18-year old Alexander Kennedy) would be burned in Glasgow in 1538, and where the renowned George Wishart would also endure death by burning in St Andrews in 1546. The intervening years also saw the deaths of many other lesser-known Scottish martyrs, for example, Henry Forrest (1533), David Stratton and Norman Gourlay (1534) and the five Edinburgh martyrs Thomas Forrest, Keillor, Beverage, Duncan Simpson and Robert Forrester (1539).

Faced with such persecution, we are told:

“… Murdoch, being in the same danger, digged and built a vault in the bottom of his own house, to which he retired himself, serving God and reading his new book. Thus he continued, instructing some few that had access to him, until the death of King James the V (note: James V of Scotland died in 1542, aged just 30, probably from cholera) … Murdoch, tho’ then an old man, crept out of his vault and joining himself with others of the Lord’s people, lent his helping hand to this work through many places of the land, demolishing idolatry where ever they came …”[1].

Nisbet’s house had been sited on land that later became Loudoun manse glebe, at the curve of a burn. Apparently there are old foundations still there, marking the location of the building.

John Nisbet the Covenanter — great-grandson of Murdoch

Murdoch died in 1558 (the year before John Knox’s tumultuous return to Scotland from Geneva) and left his New Testament manuscript to his son Alexander Nisbet, who left it to his son James, who left it to his son John. This John Nisbet was a soldier of renown, and was at Scone when the duplicitous King Charles II swore the Covenants in 1650 as part of his scheme to exploit the Covenanters and to use the Scottish throne as a stepping stone to what become his Restoration in 1660. John became a famous Covenanter hero. He was at Lanark in 1666 as the Covenanters marched toward Edinburgh, and ultimately took his stand at the Battle of Rullion Green.

At Rullion Green, John Nisbet:

“received 17 wounds, was stript naked and left for dead, yet as much strength and life reserved, as enabled him to make his escape in the night, tho’ it was a twelve month before he recovered. At Drumclog he did good service, behaved to a wonder, yet was preserved; at Bothwell he fought openly and boldly …”[2].

Time went on and John Nisbet listened to great Covenanter preachers like Donald Cargill, Richard Cameron and James Renwick, and, through the persecutions of the early 1680s, “… he contended against the sinful compliance of these times …”. He was martyred aged 58 at the Grassmarket of Edinburgh on 4 December 1685, leaving three sons, Hugh, James and Alexander.

1905: manuscript published

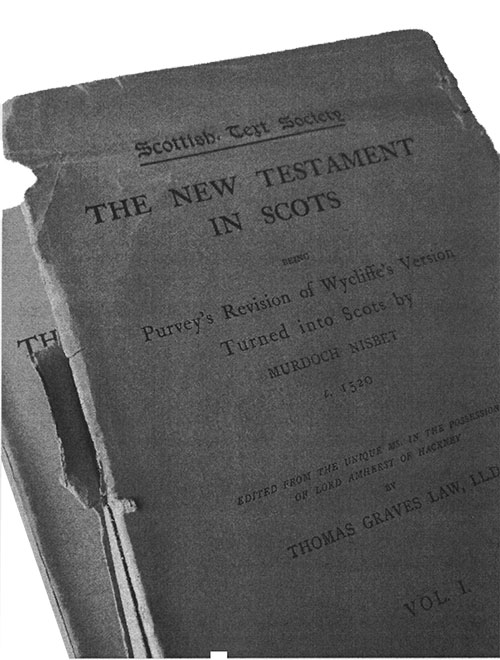

Murdoch’s old manuscript was passed down to James, who was a Sergeant at Edinburgh Castle, who gave it to Sir Alexander Boswell to keep in his library at Auchinleck in Ayrshire (only 10 miles away from where Murdoch had written it nearly 200 years before). There it stayed until 1900, when Lord Amherst of Hackney allowed it to be published by the Scottish Text Society. The manuscript is today in the collection of the British Museum.

These 1905 editions are extremely rare, but the writer has been able to obtain a copy. The translation is published in three paper-bound volumes. While it would never be of interest to anyone seeking attractive publications to grace library shelves, it is beyond price for its place in the great story of the translation of the scriptures into Scots.

Remembering the achievement of Murdoch Nisbet

The very winds of change that blew while Murdoch Nesbit lived in austerity and seclusion also sadly made his translation largely irrelevant to the believers around him when he emerged from his hiding place. Nisbet’s New Testament translation was ultimately based on the Latin Vulgate, which was the source text approved by the Roman Catholic Church, and, for those who had thrown off the influence of that church, this had been superseded by the Greek New Testament. His work had been overtaken by the pace of reform.

For those who believe in the providence of God, this presents a dilemma. Had Murdoch wasted his time? Did he misunderstand God’s will in the matter of the translation? Of course, we have no way of knowing what plans the Almighty had for Murdoch Nesbit’s New Testament, and it could well be that its message was to speak to later generations, such as our own.

Furthermore, some adherents of the persecuted church visited him in his hiding place and benefited from his teaching, no doubt enhanced and augmented by the knowledge gained in the course of the translation.

Murdoch Nisbet is remembered today in his home town of Newmilns in a number of ways. A small award-winning housing development is named after him. There is a commemorative plaque inside the local church, Loudoun Parish Kirk, which also has a number of Covenanter memorials, including one to Murdoch’s descendant John Nisbet, the Grassmarket martyr. It should be noted that parish churches in Scotland are Presbyterian.

After Murdoch’s translation

Murdoch Nisbet’s translation of the New Testament into Scots was the first ever undertaken. He had not, as stated, gone back to the original Greek or Latin, but had worked from Purvey’s English translation. For that reason, Nisbet’s New Testament is a wonderful source of information on what the differences between English and Scots

at that period were thought to be. A striking feature of the Scots translation is that to the modem eye it is actually rather more accessible than the English.

Right into the twentieth century, ministers of the Church of Scotland tended to paraphrase the English King James (or Authorised) version of the Bible to aid their Scots-speaking congregations’ understanding as it was read to them. Perhaps mainly for this reason, there was for many years no serious attempt to follow Murdoch Nisbet’s work with an updated translation into Scots.

Probably the most significant subsequent translation was that of William Wye Smith, a native of Jedburgh who spent most of his life in America. His New Testament in Braid Scots, published in 1901, was again a translation from the English. Only when William Laughton Lorimer (1885-1967), who came from Angus, worked on his New Testament translation during the 1950s and 60s, was a Scots translation undertaken that drew upon the original Greek and other sources. Lorimer died before the task was completed, and it was not until 1983 that his Scots New Testament was finally published, after his son had incorporated the revisions on Lorimer’s text. This has taken its place as one of the great works of literature in Scots in the modern era.

Notes

[1] James Nisbet, A True Relation of the Life and Sufferings of John Nisbet in Hardhill, first published 1718.

[2] Ibid.

Next: Tam's New Boots

Previous: Greetings to the Widder Town House

Contents: Ullans: The Magazine for Ulster-Scots, Nummer 12 Wunter 2011/12