And the Muse went Weaving Free

Author: Sandra Gilpin

Date: 1999

Source: Ullans: The Magazine for Ulster-Scots, Nummer 7 Wunter 1999

The Story of Robert Huddleston, Bard of Moneyrea

Sandra Gilpin

I was a small child when my father told me the story of the Poet Huddleston’s wedding in our church at Moneyrea. The bride was waiting at the Church but the groom had not turned up, so someone went to look for him. “The Poet”, as he was known locally, was found working in the field making drains. When they told him it was high time he was at the church he replied that he didn’t know it was that far on, untied the sacking wrapped round his trouser legs, left them to one side, wiped his hands to clean them and made his way directly to the church. After the ceremony, he turned to his new wife, telling her to go on up to the house as he had a piece of the drain to finish, and would be up later for a bite to eat!

Naturally this tale was followed up by a number of questions on my part: when did this all happen? What were the names of the Poet and his bride? Where did they live? What did the Poet write about? Solid facts were scarce; the tale at that time was a hundred years old and had been told to my father (Moore F. Johnston) by his grandfather (Moore Fisher, who lived between 1860 and 1951). My father was unsure of the Poet’s name, his dates or the location of his farm but knew that he had published a book of his poetry. The only fragment he believed might be attributed to the Poet was a rhyme which stated that Moneyrea had “A Preachin’ House, A Teachin’ House, wi’ the Aitin’ House between”. This described Moneyrea in the nineteenth century when Magill’s Public House was located, between the church and the National School, on the site of the present manse’s front garden.

By the early 1960s the generation that had known Huddleston personally had almost passed away. Only octogenarians who had been children when he died remained; a child myself, I never spoke to these people about “The Poet”. Their children still knew about the Poet Huddleston. The details of his life among us in Moneyrea were fading as the years passed; but I gathered that he was a man of deeply held convictions who could lampoon those with whom he did not agree. It was generally believed that his papers had been destroyed after his death and, as copies of his published work were rare, no-one really knew much about his poetry. For me he was a shadow glimpsed only obliquely in reflected images in glass, glass in windows on the nineteenth century left ajar by people like my great-grandfather, a man who died before I was even born.

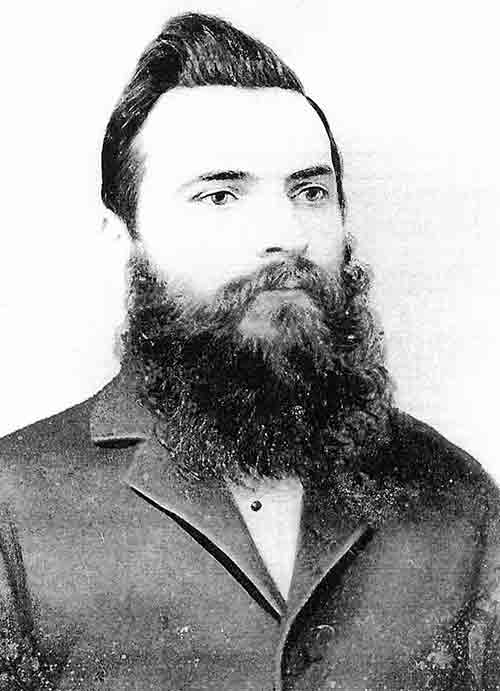

It was not until the 1980s that I saw a copy of the Poet’s poems and then only briefly. This book belonged to William James Brown, a relation of Huddleston. As a family we looked at the book with interest and noted that it was produced in the 1840s with the aid of subscriptions. Some of the poetry proved to be more difficult than we had expected; we were not familiar with seeing our speech in print, and in addition standardised English had made great inroads in Moneyrea in the intervening 140 years! It was at that time too that I saw a picture of the Poet, a bearded individual with quiff, gazing over my right shoulder in the detached, distant way determined by the technical requirements of nineteenth-century photography.

Nearly two decades passed until the day came when I happened to pick up a copy of Ulster-Scots: a Grammar of the Traditional Written and Spoken Language by Dr Philip Robinson. I noticed that this study cited the works of a variety of local poets. A strong sense of chauvinism prompted me to look for Huddleston; sure enough he was there! I duly reported back to the folk in Moneyrea: “The auld Poet’s an authority now!” In March 1999, I finally got around to seeking the permission of the committee of Moneyrea Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church to have a copy of Huddleston’s photograph made. This hand-tinted photo had been presented to the congregation by William James Brown before his death in 1994. Permission was granted and, memories jolted, we at last got a Christian name for the Poet, Robert, and found that he had lived in Moneyrea, half a mile south of the church, on a fifteen acre farm on the Tullyhubbert Road. A couple of phone calls later and I was speaking to the author of the Ulster-Scots grammar at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum. As I suspected Dr Robinson did not know that a photograph of the poet Huddleston existed; however I did not expect to find that he was acquainted with the unpublished writings of the poet, which had at some point been deposited in the Folk and Transport Museum. Unbelievably the papers which “the country” had believed lost had survived: indeed they had been for some time the object of academic study! I related the story of the Poet’s wedding and, realising that I had no facts to back it up, promised to find out what I could from the church records.

Moneyrea is located seven miles south of Belfast. It is in the Parish of Comber and in the nineteenth century was on the edge of Lord Dungannon’s Hill Trevor Estate. Since 1719 there has been a Presbyterian congregation in the area. The village has grown up around the church, and in the nineteenth century the majority of the inhabitants were members of it. Up until the middle of the twentieth century it could scarcely be called a village, as it consisted of only a handful of houses and boasted, in addition to the church, a school, a Masonic Hall, an Orange Hall, a blacksmith’s shop, a small shop, a post office and a public house. One small group of houses was known as “The Onset,” but Moneyrea itself is a townland which extends beyond the area covered by housing.

During Robert Huddleston’s lifetime the Second Subscription controversy raged in the Presbyterian Church. The minister in Moneyrea, a charismatic figure named Fletcher Blakely, supported Henry Montgomery as a Non-Subscribing Presbyterian. In fact the congregations of these two ministers in Dunmurry and Moneyrea were the first to sever their connection with the General Synod of Ulster in 1829 and were, in the following year, founding members of the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster. The term “New Light” was applied to these non-subscribing congregations who insisted on principle that ministers and elders should not be required to sign (subscribe to) the Westminster Confession of Faith. The traditional rhyme:

Moneyrea sweet and civil,

One God and no divil

and twenty shillins to the pound

refers to the liberal Christian ethos; as it is applied to chapels in England also this rhyme may have its origins there rather than in Ireland. Blakely (minister between 1809 and 1857) was a founder and joint editor of The Bible Christian, and Unitarian in his theology, a liberal in politics and undoubtedly a great influence on the young Robert Huddleston.

At the Remonstrant Synod at Narrow-Water in 1837 Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Congregations were recommended to establish libraries; this “overture” was unanimously resolved in subsequent years, Belfast 1838, Newtownards 1840 and Comber 1841. It is therefore not surprising that there is evidence of a strong reading society tradition in Moneyrea: during the ministry of Fletcher Blakely in 1830 “The Moneyrea Reading Society” was on the list of subscribers to William Anderson’s Collection of moral, instructive, and descriptive poems (Adams 1987: 124) and in 1836 it was reported in The Bible Christian that an extensive library of over 300 volumes was gathered in the Session Room. As it is unlikely that another such society existed in the area at this time it is safe to assume that this Session Room Library was the reading stock of the Moneyreagh Reading Society. Although membership lists have not survived, the young Robert Huddleston, by his own account an avid reader, was in all probability a member. According to Mr James Blair and Mr Hugh Casey, members of the Moneyrea congregation, there was a fire in this building at some uncertain date. Certainly no books dating back to the 1830s are presently in the care of the church. The old session house was demolished in 1962.

Before embarking on a search of the records held by Moneyreagh congregation I spoke to Mr James Blair (b. 1919) who now lives in County Antrim. As a child Mr Blair lived on the farm adjoining the home of the Poet’s widow. Although he was very young when Mrs Huddleston died he remembers her as “Granny Poet”. The Blair farm in Moneyrea was bought by James Blair (Mr Blair’s grandfather) following the death of his wife’s brother, Alexander McMillen, in 1895. It had a two storied thatched house with outhouses in a row which adjoined the Huddleston house. Each house had its own yard, accessed from the Tullyhubbert Road, up separate laneways on either side of a field. The Poet’s house still stands, although altered greatly. Upstairs the Poet had his study. While living there Mr Blair carried out renovations involving the removal of an internal wall. When the plaster (a mixture of lime and manure or mud) was removed, it was found to be made of peat bricks; although a fire hazard these were soundproof. In 1959 he sold the property.

Mr Blair told me that the Poet was a farmer and also made and fitted the wooden stocks of guns. The business was carried out in the upper room of the adjoining outhouse. (This was the original two-storied dwelling house on the Huddleston farm with the old fireplace still in place and internal stairway to the workshop.) Mr Blair remembers the workshop well as the equipment was acquired by his father with the purchase of the farm. Inside the workshop there was a workbench, two planks wide, and a distinctive vice designed to hold guns, with peculiarly shaped jaws to allow the gun barrel to be held vertically and two nuts to tighten the vice. He recalls one muzzle loaded gun surviving; the ram rod was badly rusted, but Huddleston’s workmanship on the stock was very fine. The equipment disappeared at the time of the auction in 1959.

Mr Blair knew of only one child of Robert Huddleston, a son who was known as “The Young Poet.” This was probably a nickname as there is no evidence that he ever wrote poetry. He lived an unsettled life, emigrated to America and died young as a result of a shooting incident following a dispute. Mr Blair said that at the turn of the century Mrs Huddleston brought up a young girl called Bessie Boucher, whose mother had died when she was very young, but he was unsure of their relationship. Bessie married a Moneyrea man named Dickson (in London) and emigrated to Australia after the First World War. Bessie maintained contact with her friends in Moneyrea, and her son John has visited the area.

Armed only with the knowledge that Mrs Huddleston had died in the 1920s, we contacted Mr Hugh Casey, the former Church Secretary, whose knowledge of the church records is second to none, and he advised us throughout the search. There are no records of individual burials available prior to 1920; but a Record of Burials book compiled by Mr Andy Lappin (Sexton) notes a burial in 1922 in Section B, Row 2 plot 20, of Margaret Huddleston, aged 80 years. In the three graveyard registration books we found Section B, Row 2 plot 20 (three graves) registered in the name of James Huddleston, Moneyrea. This grave plot was transferred by the Church Committee in 1924 to Mrs Bell, 113 Bellevue Street, Belfast. In the same hand the words “Poet Huddleston” were written, probably by the Church Secretary at that time, who was Samuel McKenna Turkington, a neighbour of the Poet’s widow and an executor of her will. In the 1948 Graveyard Registration Book Plot 20 was registered in the name of Mrs Boyd, “Adjilon”, Caledonia Road, Ayrshire.

In the marriage register we discovered that Robert Huddleston of Moneyrea (father: James Huddleston, farmer) and Margaret Jane Ellison of Moneyrea (father: James Ellison, farmer) were married by Rev John Jellie on 28th February 1862. A quick calculation puts Margaret Jane at almost twenty that day while Robert was nearly fifty.

Records of baptisms prior to 1864 were not available, while between 1885 and 1888 no baptisms were recorded. The only child of Robert and Margaret found in the Baptismal Register was Nancy (the diminutive form of Agnes), born 1st March 1865, baptised on 6th April by Rev David Thompson. There was no record of either the son who died in America or Mary. (According to Robert Huddleston in an unpublished poem she was born on 11th March 1868.)

Recording of stipends was erratic. In 1916 there is a record of Mrs R Huddleston (Pew No 40); in 1924 she is not listed as a stipend payer. Confirmation that this was the pew held by Robert Huddleston was obtained by Moore F Johnston from surviving Annual Reports:

1885 Pew 40 (2 years) stipend paid by Robert Huddleston (14s 3d);

1886/1887 Pew 40 stipend paid by Robert Huddleston (7s 11/2d);

1887/1888 Pew 40 stipend paid by Mrs Robert Huddleston (7s 11/2d);

1921/1922 Pew 40 stipend paid by Mrs Robert Huddleston (8s 0d);

1923/1924 Book not found;

1923/1924 Pew 40 Mrs Robert Huddleston not listed.

The names and dates were consistent with the information we had at this point, which was that a Mrs Robert Huddleston died in the early 1920s and her husband died in 1887. However, we had to wait another week to confirm that we were looking at the correct records, as only then could we examine the Huddleston family headstone.

Moneyrea-Graveyard is very well maintained and the records are good. When we went to Section B Row 2 we discovered that the headstone had fallen, and only the base was visible. The Church Committee gave permission for this headstone to be uncovered and turned. Although the stone had broken, the inscription on the headstone and plinth was easily read:

Erected

By

James Huddleston

of Moneyrea

in memory of his Son John

who departed this life

8th February 1836

in the 26th year of his Age.

The mortal remains of James Huddleston

who erected this stone now moulder

beneath the turf which it marks,

he died 21th* [sic] March 1851 Aged 73 years.

Also the remains of his Wife Agnes,

who died 27th March 1861 Aged 70 years.

His son Robert Huddleston

died 15th February 1887 Aged 73 years.

Margaret Jane Wife of Robert Huddleston

died 9th September 1922 Aged 80 years.

(on base/plinth)

Their children Mary Huddleston

died 18th July 1877, Aged 9 years.

(Mrs) Agnes Boucher, died 21st August 1897, Aged 32.

Robert Huddleston, 1814-1887

(Photo courtesy of Moneyrea Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church)

The next step was to look at documents held in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland in Balmoral Avenue, Belfast. My father and I spent two afternoons there and examined wills and census returns.

The will of Robert Huddleston of Moneyrea is held on microfilm at the Northern Ireland Public Record Office (No. Mic/15c/2/27). It was proved by John Boucher of Monlough on 11th March 1887, and confirms that, at the time of writing (13th February 1885), Robert Huddleston’s wife, a daughter and son were still living; however, only Nancy is named. It is a standard farmer’s will, concerning itself with the tenancy, and does not yield a great deal of additional information.

The will of Margaret-Jane Huddleston of Moneyrea (also at the Northern Ireland Public Record Office), probate granted to David Huddleston and Samuel McKenna Turkington on 9th September 1922, proved to be much more interesting. This will is in a packet containing: a schedule of particulars of buildings and lands with Inland Revenue affidavits leading to grants of probate or administration; Estate Duty accounts; and succession accounts where no Estate Duty is payable; two papers relating to the redemption value of annuity under the Land Purchase Act; a list of monies due under promissory notes; and details of money deposited in a Belfast bank. A separate envelope contains the original handwritten will and an oath for the executor confirming its authenticity. At the time of her death Margaret Jane “left no husband, no lawful children, four other more remote lawful issue, no lawful parent or grandparent her surviving”. This confirms that her children had pre-deceased her. Margaret Jane’s will provides evidence of the identity of Mrs Mary Bell, daughter of John Boucher (and therefore daughter of Agnes or Nancy), as a granddaughter of Robert Huddleston. It is stated that Mrs David Dickson was also a granddaughter, and daughter of John Boucher. This is Bessie Boucher, mentioned by Mr Blair, whose mother Nancy died while she was an infant. Two other grandchildren are named: Joseph and Margaret-Jane Huddleston, the children of James (the son of Margaret-Jane and the Poet Robert Huddleston). In addition to providing details of family relationships of beneficiaries, the will contains instructions concerning the papers of Robert Huddleston: these were entrusted to Samuel McKenna Turkington along with the cabinet in which Robert Huddleston stored them. These are the papers which are now held by the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum.

The 1901 census return reveals that at this time James did not live on the farm at Moneyrea. There are two residents on the night of the census: firstly, Margaret Jane Huddleston, head of household, Unitarian, who can read and write, aged 57, female, occupation farmer, widow, born in Co Down; and, secondly, Robert Davy, servant, Roman Catholic, who can read and write, aged 29, male, occupation farm servant, not married, born in Co Down. The return is signed by Margaret J. “Huddleston.”

This ambiguity in the spelling of the name Huddleston is typical. Robert, not the most consistent of spellers, always used the form “Huddleston” but the records vary widely: “Hiddleson,” “Huddleson,” “Huddleston” (Clarke 1966:76). One branch of the family used the form “Huddleson” on the mourning card of the husband and “Huddleston” on that of the wife. Even the name of the village underwent a change when in the 1960s the spelling “Moneyreagh” was introduced.

A mourning card for the Poet survives in a collection kept by the Anderson and, later, McCullough families of Moneyrea. Amongst the surviving cards, the names of several people connected with Huddleston appear: the Poet’s neighbour Alexander McMillen (d. 1895), Grace Blair (d. 1899, née McMillen and sister of Alexander), James Blair (d. 1902, husband of Grace), Elizabeth Orr (d. 20th August 1872, daughter of the Poet’s friend Gawin Orr — Huddleston wrote a poem “In memory of Miss Elizabeth Orr and Miss Minnie Fletcher” originally published in the Northern Whig in 1874). Robert was a popular Christian name amongst the Huddlestons in the area. In the collection of mourning cards evidence for three others survives:

Robert Huddleston of Monlough d. 1896 (aged 66), husband of Mary, née Frame (m. 10th March 1874);

Robert Huddleston of Ballykeel d. 1897 (no age given), husband of Sarah;

Robert A Huddelston of Moneyrea d. 1907 (no age given), father of Samuel (husband of Mary, d. before 1871, and Agnes, d. 1896).

The only descendant of Robert and Margaret Jane Huddleston to whom I have spoken is Mr John Dickson, son of Bessie and David Dickson and the youngest of their three children. From Mr Dickson I learned that Mrs Bell and Mrs Boyd mentioned in the Moneyrea Church records were one and the same person. This was his Aunt Mary, who had been widowed and subsequently re-married. Mr Dickson had no knowledge of the other branch of the family, the children of “the Young Poet” James Huddleston — there may be descendants of Robert Huddleston in the United States of America.

Among the Moneyrea folk I spoke to there was a great curiosity about the Poet’s works. He was remembered as being “a great powerful man,” and people were naturally anxious to hear his own voice. The surviving papers in the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum (copies of letters, poems, and even a novel, as well as some work by “John Huddleston, Gunmaker — Ballynahinch” — possibly Robert’s older brother) cannot be digested in a few afternoons. The focus of my reading of his unpublished work has been quite restricted: I have so far ignored the novel, many of the letters which were written to friends outside the area, and the overtly political poems, and have concentrated on works with local references or those mentioning the Poet’s family and friends. Perhaps this has been no bad place to start, as in these Robert Huddleston bares his soul and shows himself to be a sensitive individual, sometimes prone to melancholy, whose inner imaginative world was a solace and even a source of delight, but at all times the vital part of his life. Already I have revised several opinions, but a definite idea of what the poet Huddleston was like has formed in my mind.

So what have I found? Robert Huddleston both reflects and illuminates his community: he is radical in both religion and politics — as most of his neighbours were — but through his writing he is the only one who has allowed us to hear that voice. He gives tantalising hints of the debates which fired their social gatherings and records the minutiae of a way of life that proves to be less inward looking, isolated and conservative than we might tend to assume. Although Huddleston may not have had many opportunities to travel (although we do know he crossed the Irish Sea at least once from one song), he peppers his works with exotic references to places such as the Andes and Pitcairn’s Isle, besides corresponding with friends who have emigrated to America. His reading of the newspapers such as the Northern Whig gave him a good knowledge of current affairs. (He used newspaper to bind some of his poems and even an obituary clipped from the Northern Whig has been preserved!) The young Bob was convivial and evidently enjoyed life to the full. He writes in a letter to John Poundley in September 1843 that he has been made lame by a “mettle bullet”, probably as early as 1835. The game of bullets has disappeared in the area: the car now reigns supreme on the Ballygowan to Belfast Road, where the teams once gathered for their tournaments. However, in his thirty second year he wrote an “Epistle to a Friend,” describing how he has taken stock of his life, and declared his intention to:

“… begin the walk of life anew, and select my friends for the future Now that I am at the forked road, from which I started in life’s morning I will try the other passage to the tomb and see if the prospects are more cheery as I proceed along …”

“Epistle to a Friend” (1845 or 1846)

In Huddleston’s day the main Comber to Carryduff road was crossed by the narrower road running from the church to Huddleston’s home and then continued on to Saintfield. That it was this “Lang X” which inspired him would appear to be confirmed in a very long poem in which he describes an ecstatic experience occurring beside his neighbour’s thorn at this crossroads:

I thought I stood on dazzling stones

And all around was bright

The prettiest skirts and rarest dyes

Spread through the gloom o’ night …

“Apparition and Sermon… ”

A voice speaks to him from the thorn and through it Huddleston sets out his thoughts on faith. The voice tells him to:

Repent for misdeeds gone and past

For time to come reform …

The resolutions made appear to have been carried through, and he increasingly adopts a high-minded, if not moralising, tone on a variety of subjects. To take one example, his attitude to drink changes: the sentiments expressed in his poem in praise of “Auld Comber” whiskey can be contrasted with his condemnation of “bousing” in “With sorrowful heart at the follies of man”!

His changing attitude to death is striking: the young man who could in his thirties instruct the stonemason to inscribe the words “moulder beneath the turf” on his father’s headstone, who could robustly consider his own declining years and death, stating “I want no tears for I’m full of years”, and who, moreover, judges that:

Man beyond three score is only a bore

Then why should he longer last?

knows better when he himself approaches that stage in life:

Death, the pale warrior nane can withstan’ …

Death is a monster, ’tis much to be feared

“My freens all gane, I am left alane”

More poignantly, the “auld kirk yard” that was dear to him, a place where he mused and let fancy play, the spot he had loved as it nestles a’ his ain, three decades later contains his wean Mary, and he cannot:

gang whare Mary rests,

Far less the yard gae by

“Mary on the Brain”

His poems in memory of this child describe the experience of grief in a way that is authentic and therefore powerful:

There’s not a bonnie flower springs

But her remembrance brings

There’s not a bonnie bird that sings

But what of Mary sings

There’s not a spot in all the farm

A dyke tree, mound or stone

But Mary’s here and Mary’s there

For Mary’s on my brain

“Mary on the Brain”

Another poem entitled “My darling little child” is worthy of mention. In it Huddleston speaks as a mother whose firstborn “only ba” has died. Whether or not it was written before Robert Huddleston experienced the loss of a child it shows remarkable sensitivity and insight into the heart of a grieving parent. Writing with fluency he articulates the mother’s grief and her reaction to clumsy expressions of sympathy which do not acknowledge the full reality of her loss. Here we see that Huddleston’s faith in God’s mercy never waivers: it is his consolation in dark and bleak moments of despair. This poem may well be autobiographical. Perhaps Huddleston was initially reluctant to express paternal grief, and so adopted a female voice. The child who is mourned is named as Mary, but this could not be the Mary Patterson Huddleston whose name appears on the family headstone, the nine-year-old younger sister of Nancy. We can infer that Robert and Margaret Jane lost their first child and called a later child Mary also; however, no records have been found to confirm or refute such speculation.

At the time of the publication of his books (between 1844 and 1846), while he was still in his early thirties, Huddleston appears to have believed he was about to marry. A faded draft New Year’s greeting on the cover of one manuscript makes reference to the clothes he intends to buy for the event with the profits of his next publication. Is the “spirited lassie” his “ain Lass,” the girl he writes to from the garret off Mill Street in Comber? Perhaps she is also the other party to the relationship of which he writes in a number of poems (a “Song to Jeanie”, “In the parish of Comber”, and “Verses written on disappointed affection”). It would appear that the intended bride did not wait for him to make his fortune and left Huddleston emotionally wounded. He even considers leaving Ireland altogether as many from the area, including his friend and neighbour James Ball, were to do:

Though fortune be cruel

And woman untrue

Yet as sweet a fair lassie

As her may me lo’e

And she yet may be joyless

While I may be gay

And far, far from Erin

And blythe Moneyrea

At this same period he looks for a way out of farming, asking J Dunlop in 1846 if he can get him a position on the Downshire Railway when it commences. In his poems many girls’ names appear, but it is impossible to know how many of these refer to actual romantic attachments. As the years pass he apparently accepts that he is fated to die single, even stating: “I’m the last of all my race”. However, the sisters of the spinner had a different plan for the Poet, and on November 12th 1861 he wrote his lines to Margaret Jane.

This is the bride we started with, the girl standing in the Church waiting for her groom to appear: the girl who outlived her parents, her husband and her children to survive into the third decade of the Twentieth Century. To the “country” it appeared that the Poet was giving her less than her due — after all this is the man who wrote in a letter in 1846, “If a woman is not kept in her place she will knock man out of his”! However, reading the words Robert Huddleston wrote to his betrothed, it is obvious that the face he showed to the world that day was not the whole story. He promised her: “I’ll do my best life tae mak’ sweet”. Perhaps that day, waiting in Moneyrea Meeting House, Margaret Jane already held in her hand the bible in which he had inscribed a poem which included the words:

I love — whom do I love but you?

You’ve vowed your love — sworn to be true …

Our pathway is both dark and drear

Yet were a thousand suns to shine

Could I be dearer yours — you mine!…

A present from the rhyming swain

’Tis given in love to Margaret Jane

“Lines wrote on the fly leaf of a Bible”

Writing three months before his wedding day in the winter of 1861, Huddleston is sensitive about the comments of the “hardy world”: he is acutely aware that while his future wife is “no twice ten till May” he is “auld and that’s the woe”. His criticism of young girls who took husbands of “mature” years was the subject of his earlier poem “An advice tae the lasses I will gi’e”. He knew his words could come back to haunt him; but like many a one before him he shrugs his shoulders, abandons his shibboleth and concludes:

But when the youth can love the age —

Oh, how can I say no ?

“Margaret Jane”

As he made his way home from the penns that February evening there was a new life ahead of him, a life that would, as we have already noted, hold sorrow; but that sorrow was the weft while joy was the warp on his loom of life: a life from then on to be shared first with a wife and then with their children.

Leaving aside all judgements as to the literary merits of the work (or in some cases its lack) Huddleston is, from the point of view of the local historian, an invaluable resource. He comments on political, religious and social events as his century unfolds. Name practically any subject and he has an opinion on it: hare coursing, capital punishment, exploitation of tenants, clergy who put the letter of the law before the spirit, hypocrisy and narrow-mindedness in all its forms. Taken as a whole the papers become a sort of poetical diary charting the development of the young man, full of high hopes and literary ambition, into the older, wiser man. Huddleston felt things both passionately and deeply, and poured out his thoughts and feelings onto paper often: “Till the cock loud crowed for day”. The recognition which so persistently eluded him during his lifetime is finally being given — an entry for Robert Huddleston by Dr Ivan Herbison is to appear in the 2002 edition of the “New Dictionary of National Biography”. You might say that a Moneyrea Bard has made good!

Through the papers so carefully deposited over the years in the Poet’s cabinet we no longer stand under the old alder tree waiting to catch a reflection in the window panes. By turning the page we can tiptoe inside the little lamp-lit study in Moneyrea to peep over the shoulder of the bard whose muse went “weaving free”: the shadow has been given substance.

Next: Verb Endins

Previous: European Programme for Minority Languages

Contents: Ullans: The Magazine for Ulster-Scots, Nummer 7 Wunter 1999